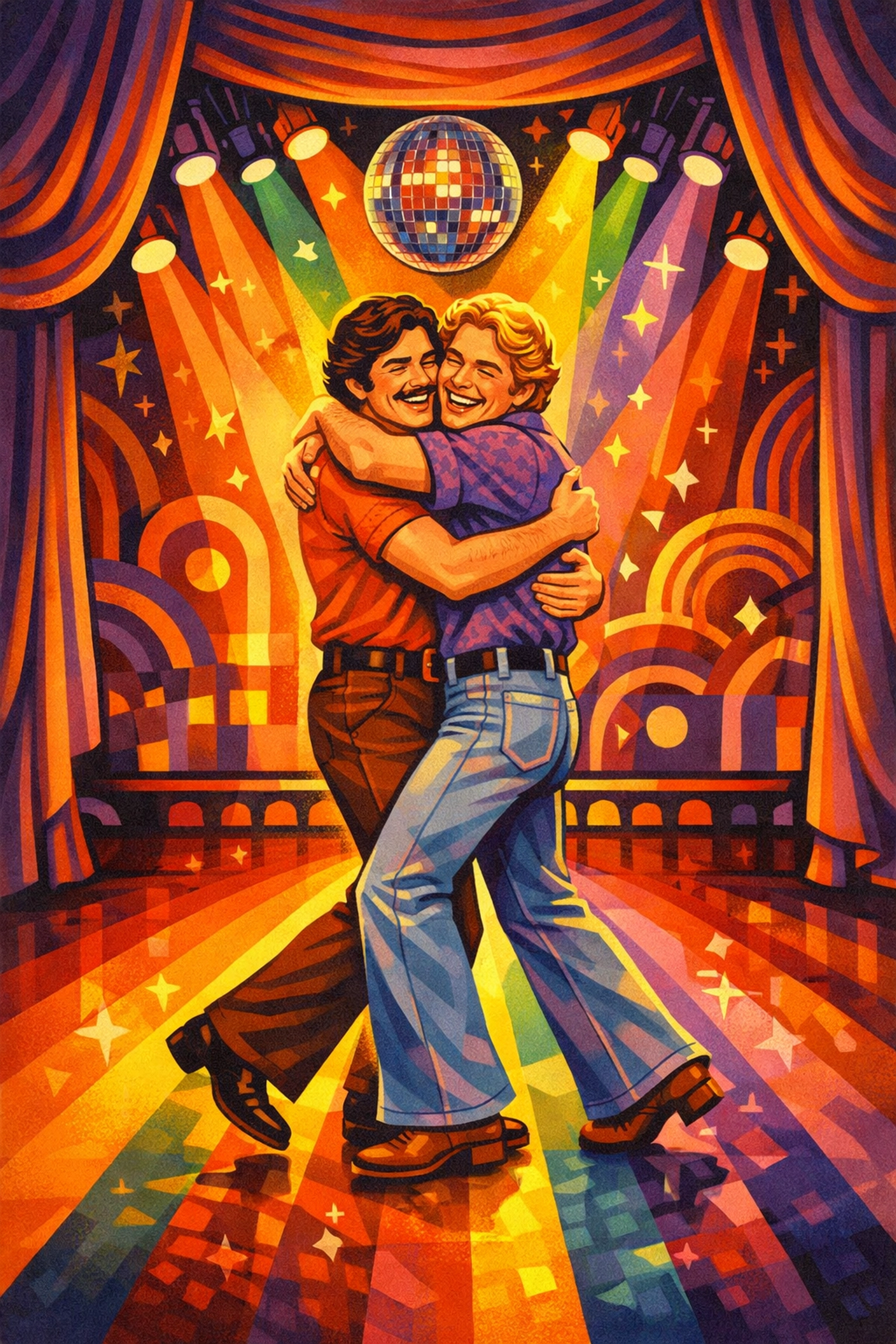

Long before Pride parades filled city streets and rainbow flags flew openly, theatre stages provided something precious and rare: a space where queer people could exist, even if only in whispers and coded gestures. The footlights illuminated stories that couldn't be told anywhere else, and the anonymity of the darkened audience created a temporary sanctuary where queer folks could see themselves reflected back: sometimes tragically, sometimes triumphantly, but always seen.

Theatre has always been inherently queer. The art form itself required men to play women for centuries, demanded emotional vulnerability in a world that punished it, and created temporary worlds where different rules could apply. It's no accident that so many LGBTQ+ people have found their home in the theatre: both as creators and audience members. Let's pull back the velvet curtain and explore how theatre became one of the first safe spaces for queer expression.

The Dangerous Early Days (1920s-1950s)

The 1920s and 30s saw the first whispers of explicit queer content on mainstream stages. Plays like The Drag and The Captive dared to explore homosexuality, though always through a lens of tragedy. The message was painfully clear: deviate from heterosexual norms, and you're destined for sorrow. Not exactly the uplifting gay romance novels we celebrate today at Read with Pride, but it was a start.

Then came the "Pansy Craze": a brief, glorious moment in vaudeville when queer performers could be openly flamboyant on stage. But like many good things in queer history, the backlash was swift and brutal. From the 1930s through the 1960s, queer theatre was forced underground, existing "in direct defiance of explicit legal bans, produced in secrecy or through coded language, existing in the literal and figurative shadows."

Imagine creating art while constantly looking over your shoulder. That was the reality for queer theatre makers for decades. They developed their own language: coded gestures, knowing glances, double entendres that sailed over straight audiences' heads but landed perfectly with queer ones. It was theatre within theatre, a secret show for those who knew how to look.

Even as late as 1957, when the Wolfenden Report recommended decriminalizing homosexuality, it remained impossible to show same-sex relationships on stage. But theatre makers are nothing if not resourceful. Shelagh Delaney's A Taste of Honey (1958) featured Geof, a gay student portrayed with sensitivity and nuance: not as a stereotype or tragic figure, but as a human being. It evaded censorship and cracked open a door that would soon swing wide.

The Watershed Years (1967-1970s)

Everything changed in 1967. Decriminalization in England and Wales meant queer artists could finally emerge from the shadows without fear of arrest. Tragically, that same year saw the murder of Joe Orton, whose dark comedies had pushed boundaries and would continue to inspire generations of queer theatre makers.

Across the Atlantic, 1968's The Boys in the Band offered audiences an unfiltered glimpse into gay men's lives: messy, complicated, and achingly real. Meanwhile, Cabaret's gender-fluid Master of Ceremonies became a queer icon, proving that challenging gender norms could be both theatrical gold and politically powerful.

But perhaps the most significant development was the founding of Gay Sweatshop in 1975. This groundbreaking company set out to create work actively exploring gay and lesbian experiences in the UK. They toured the country, taking queer stories to places that had never seen them, challenging stereotypes and opening minds one performance at a time.

The 1970s also saw the abolition of theatre censorship in Britain, and suddenly venues like The Drill Hall could openly platform gay, lesbian, and bisexual work. Drag performers transitioned from nightclub stages to legitimate theatres. The feminist theatre company Siren emerged. Theatre was becoming genuinely, gloriously queer.

Coming Out Into the Mainstream (1980s-1990s)

The 1980s brought Torch Song Trilogy, giving audiences a gay protagonist who demanded to be taken seriously. But the decade also brought devastation: the AIDS crisis. Theatre responded before film or television had the courage. Louise Parker Kelley's Anti Body (1983) became the first play to address AIDS, creating space for grief, anger, and activism on stage.

By 1986, La Cage Aux Folles played London's Palladium: drag had officially gone mainstream. Jackie Kay's Twice Over (1988) became Gay Sweatshop's first play by a Black playwright, beginning to address the intersectionality that had too often been ignored in queer theatre.

The 1990s gave us Angels in America, Tony Kushner's epic masterpiece that portrayed LGBTQ+ experiences with unprecedented authenticity and depth on Broadway. These weren't the tragic queers of early theatre or even the defiant activists of the 70s: these were complex, fully realized human beings whose stories deserved the biggest stages in the world.

Just as MM romance books and gay fiction were beginning to flourish in bookstores, theatre was claiming its space in mainstream culture. The parallels are striking: both mediums fighting for the right to tell queer stories with nuance, joy, and yes, happy endings.

The New Millennium: Theatre Gets Even Queerer (2000s-Present)

The 21st century has seen an explosion of queer theatrical expression. Above The Stag, founded in 2008, became Europe's first full-time producing LGBT theatre. Rikki Beadle-Blair's Bashment (2005) tackled homophobia in hip-hop culture, while his Summer In London (2017) featured the first full-scale show with an all-trans cast on a mainstream UK stage.

Laura Wade's 2015 adaptation of Tipping The Velvet was an upfront, unapologetic celebration of sexuality: no coded language, no tragic endings, just queer joy and desire center stage. Today's theatre reflects the diversity of the LGBTQ+ community in ways early pioneers could only dream of: trans stories, non-binary characters, queer people of color, disabled queer folks: all claiming their space in the spotlight.

Contemporary queer theatre functions as what one artist beautifully describes as "temporal fleeting spaces, both spiritually and literally, where we can come together as a community and find safety and love and joy and sex and art." It's a counterforce to oppression and a space for expression, community, and political defiance.

From Stage to Page: The Storytelling Continues

The history of queer theatre mirrors the journey of gay literature and MM romance: from coded and hidden to celebrated and mainstream. Just as theatre provided safe spaces for queer expression when few others existed, gay romance novels and LGBTQ+ fiction offer readers that same sense of recognition and belonging.

Whether you're watching two men fall in love under the stage lights or reading about them in a steamy MM romance book, you're participating in a long tradition of queer storytelling that refuses to be silenced. The best gay fiction, like the best queer theatre, doesn't just entertain: it affirms, challenges, and transforms.

Theatre taught us that queer stories deserve grand stages, complex characters, and yes, happy endings. Every MM novel, every piece of gay contemporary romance, every LGBTQ+ ebook carries forward that legacy. We've come from whispering in shadows to shouting from rooftops: or at least from bestseller lists.

Want to explore more queer stories? Check out our collection of MM romance books and gay fiction that carry forward theatre's proud tradition of authentic queer storytelling. From historical romance to contemporary love stories, we've got the happy endings the early theatre pioneers could only dream of.

Follow us for more LGBTQ+ content:

- Facebook: Read with Pride

- Instagram: @read.withpride

- X/Twitter: @Read_With_Pride

#ReadWithPride #MMRomance #GayRomanceBooks #LGBTQBooks #QueerTheatre #TheatreHistory #GayFiction #MMRomanceBooks #QueerHistory #LGBTQHistory #GayLiterature #QueerStories #TheatreLove #MMContemporary #GayBooks2026 #LGBTQPride #QueerCommunity #GayAuthors #MMNovels

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.