readwithpride.com

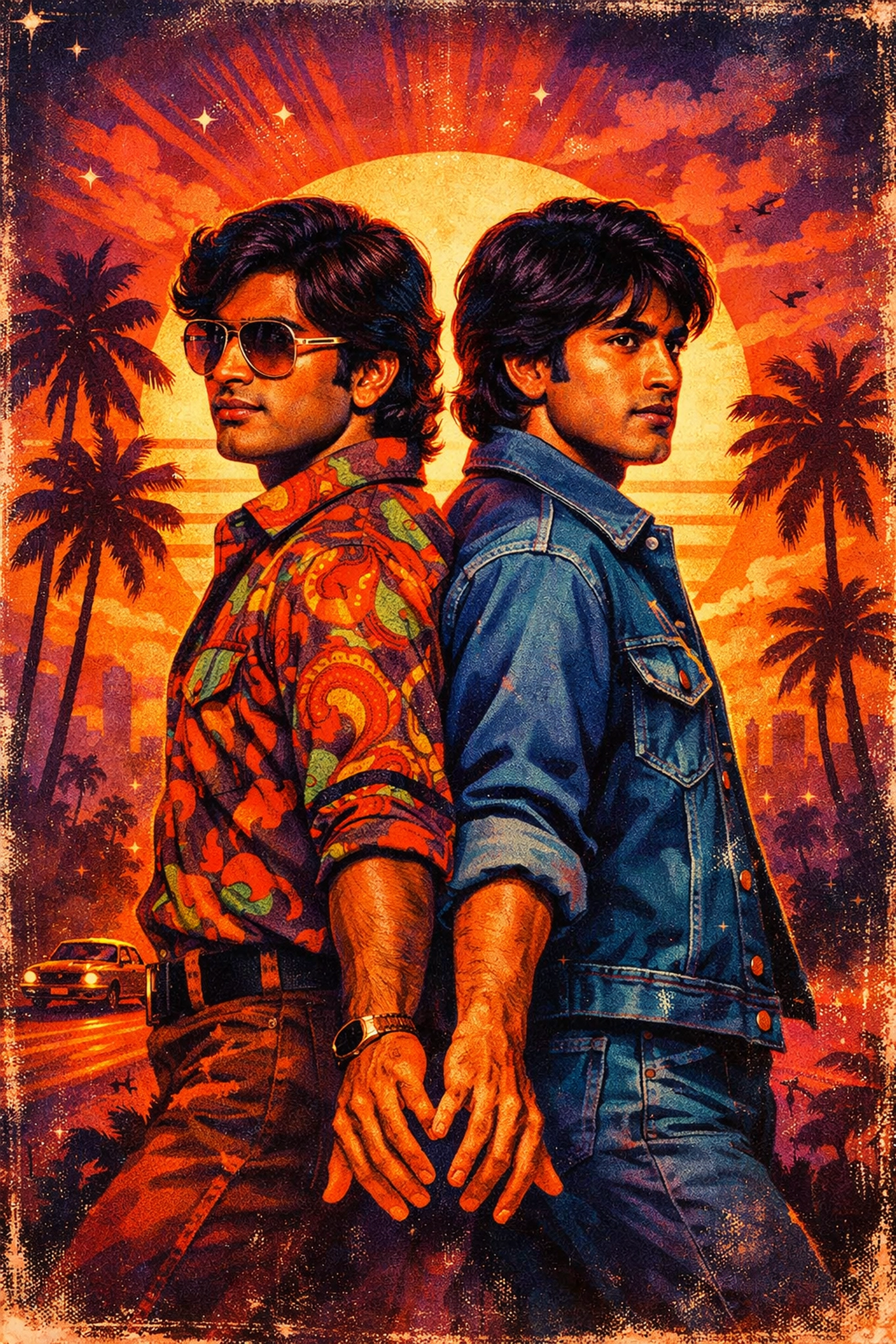

There's a word in Hindi that carries more weight than most friendships can handle: yaar. It's a term of endearment, a declaration of loyalty, a promise that extends beyond blood. In Bollywood's golden age: and honestly, still today: yaari (friendship) between men has been depicted with an intensity that would make most romance novels blush. The lingering looks, the desperate promises, the willingness to die for each other… it's all there, dressed up as "just friendship."

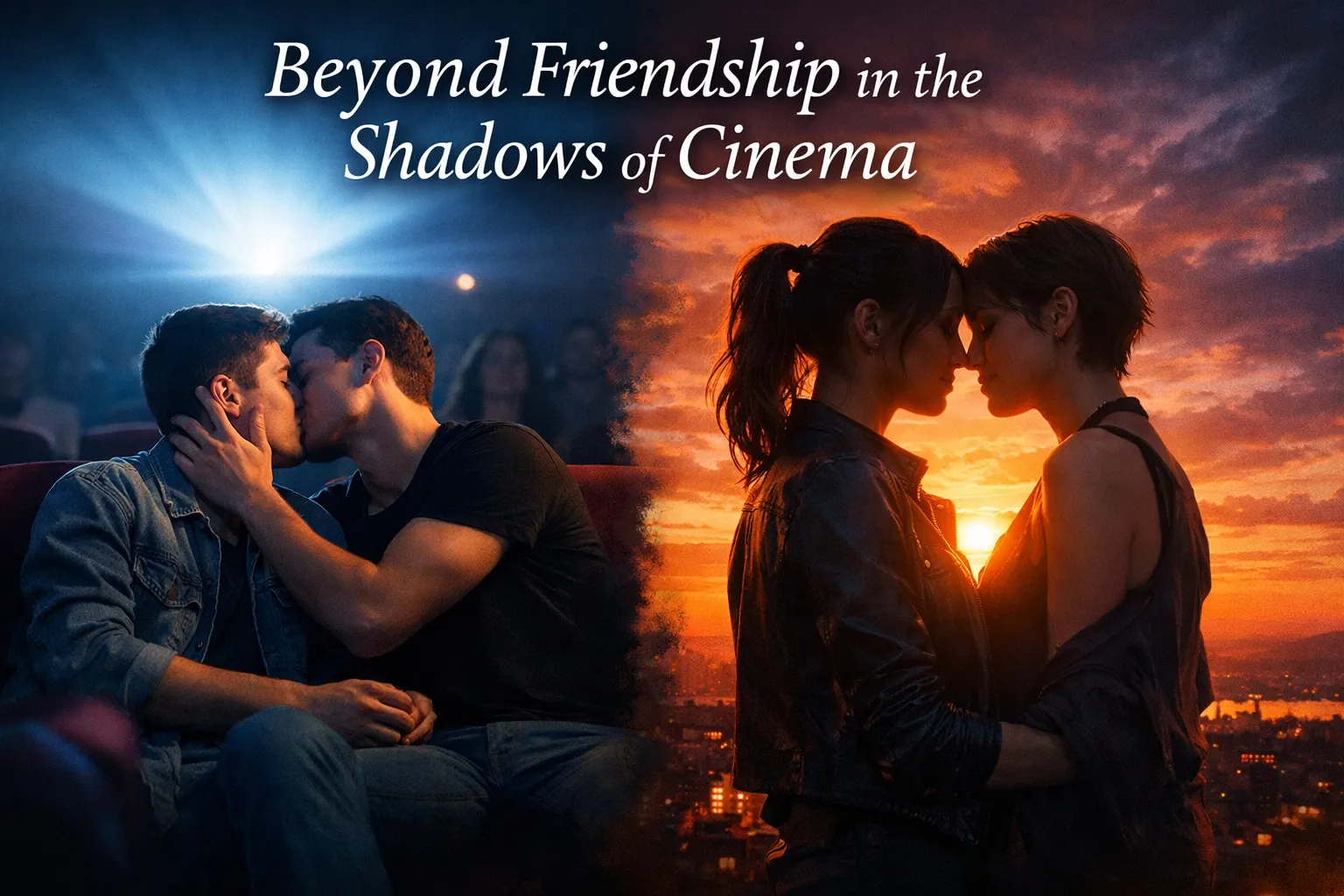

But here's the thing: when you watch these films through a queer lens, something shifts. Suddenly, you're not watching two friends: you're watching a love story that couldn't speak its name.

The Language of What Cannot Be Said

Classic Bollywood understood something profound: when you can't say it directly, you say it through everything else. The camera angles, the music swelling at just the right moment, the way two men's hands almost: almost: touch. It's the art of subtext taken to operatic heights.

Think about Sholay (1975), arguably one of the most celebrated films in Indian cinema. Jai and Veeru's relationship is the emotional core of the movie. They're inseparable, they understand each other without words, and when tragedy strikes, Veeru's grief is more raw than any romantic subplot in the film. The famous coin-flip scene where they decide who gets to pursue Basanti? It's played for laughs, but there's an undercurrent of something deeper: a negotiation between two people whose bond supersedes any heterosexual romance.

Or consider Dosti (1964), a film literally titled "Friendship." Two boys, one blind and one disabled, navigate life together with a devotion that transcends survival. They complete each other in ways that the film treats as more meaningful than any romantic pairing. The emotional climax comes not from finding love, but from the fear of losing each other.

When Brothers Become Everything

Bollywood has a fascinating obsession with the "brothers who aren't brothers" trope. They meet, they click, they become yaars, and suddenly they're more important to each other than their actual families. The ritual of rakhi (a brother-sister bond) gets subverted into male friendships that operate on their own plane of existence.

Dil Chahta Hai (2001) brought this dynamic into the modern era. Three friends: Akash, Sameer, and Sid: whose relationship with each other is the real love triangle of the film. When they fight, it's devastating. When they reunite, it's cathartic. The women in their lives come and go, but their bond is presented as eternal, unshakeable, and frankly, more cinematically interesting than any of their romantic pursuits.

The queer reading isn't a stretch here: it's almost unavoidable. When Sameer sings to Akash, when they hold each other during moments of crisis, when they can't imagine life without each other… these are the beats of a romance. The film doesn't acknowledge it as such, but the emotional architecture is identical.

The Tragedy of Almost

What makes these films particularly poignant from an LGBTQ+ perspective is the tragedy of proximity. These men are allowed to be everything to each other: except lovers. They can share beds, wear each other's clothes, weep in each other's arms, but the one thing they cannot do is name what they are.

In Kal Ho Naa Ho (2003), the dynamic between Aman and Rohit is played for humor when Rohit's mother misunderstands their relationship. The joke is that two men could never be together: how absurd! But watch the film again. Watch how Aman orchestrates Rohit's happiness with Naina, how he sacrifices his own desires, how his love expresses itself through self-erasure. It's a queer narrative hiding in plain sight, using heteronormative coupling as a beard for deeper feelings that can't be explored.

Cultural Context: Where Love Dares Not Speak

To understand why Bollywood coded queer love as friendship, you have to understand Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code: a colonial-era law that criminalized "carnal intercourse against the order of nature." From 1860 until its partial reading down in 2018, being openly gay in India wasn't just taboo; it was illegal.

Filmmakers who wanted to explore same-sex intimacy had to be clever. They had to disguise it, to present it as something societally acceptable. Deep male friendship was celebrated in Indian culture: it had literary precedent, it had mythological resonance (Krishna and Sudama, Ram and Sugriva). So that's where queer narratives hid, in the shadow of cultural acceptability.

The result is a cinematic legacy where queer audiences learned to read between the frames, to see ourselves in stories that weren't technically about us. We became experts in subtext, in recognizing the signs: the intensity of eye contact that lingered too long, the jealousy over a yaar's romantic interest, the physical intimacy that exceeded "normal" friendship bounds.

Modern Whispers of Change

Contemporary Bollywood is slowly: painfully slowly: beginning to acknowledge what was always there. Films like Aligarh (2015) and Ek Ladki Ko Dekha Toh Aisa Laga (2019) directly address LGBTQ+ themes, though they still approach them with a certain gentleness, a carefulness that suggests the ground beneath is still unstable.

But here's what's fascinating: even as Indian cinema becomes more explicit about queer narratives, the yaari films continue. Because they serve a dual purpose: they satisfy queer audiences looking for representation, and they satisfy straight audiences who see them as celebrations of platonic male bonding. Everyone gets to see what they want to see.

The Power of Queer Readings

What these films demonstrate is that representation doesn't always require explicit acknowledgment. Sometimes it lives in the margins, in the subconscious of the text. And for decades, that's all many of us had.

Reading queer love into Bollywood's great friendships isn't about forcing an interpretation where none exists. It's about recognizing that love: real, deep, transformative love: looks the same whether it's allowed to be romantic or not. The feelings are there. The devotion is there. The "I would die for you" dramatics are definitely there.

For queer audiences, particularly in cultures where being openly gay remains challenging, these films offered something crucial: proof that our feelings were big enough for the big screen. They validated the intensity of our connections, even if they couldn't name them accurately.

Where Do We Go From Here?

As India continues to evolve on LGBTQ+ rights: marriage equality is still being debated, adoption rights remain contested: Bollywood's role becomes more complex. Will it lead the conversation or follow it? Will new films continue to hide queer love in friendship, or will they finally give these dynamics the recognition they deserve?

The answer is probably both. Cinema is a mirror and a window, reflecting society while also imagining what it could be. The yaari films of the past weren't just substitutes for representation: they were their own form of resistance, a way of saying "this love exists" without saying it directly.

For readers of Read with Pride, these films offer a fascinating study in coded narratives. They're the cinematic equivalent of MM romance novels that couldn't quite be MM romance. They're love stories in everything but name, and that makes them both heartbreaking and oddly triumphant.

Because here's the truth: love persists. It finds ways to express itself even when the culture says it shouldn't exist. And sometimes, in the shadows of cinema, under the guise of friendship, it burns brightest of all.

Explore more LGBTQ+ stories, gay romance novels, and queer fiction at Readwithpride.com. Follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and X/Twitter for daily content celebrating authentic queer narratives.

#ReadWithPride #MMRomance #QueerBollywood #LGBTQIndia #GayRomanceBooks #BollywoodHistory #QueerCinema #YaariLove #GayFiction #LGBTQFiction #IndianLGBTQ #QueerReading #MMRomanceBooks #GayLoveStories #BollywoodFriendship #QueerSubtext #GayBooks2026 #LGBTQRepresentation #AuthenticQueerStories #ClassicBollywood

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.